I: A LABYRINTH AND AN ABYSS

Jorge Luis Borges, from Pascal’s Sphere:

“In that dejected century, the absolute space that inspired the hexameters of Lucretius, the absolute space that had been a liberation for Bruno was a labyrinth and an abyss for Pascal. He hated the universe and yearned to adore God, but God was less real to him than the hated universe. He lamented that the firmament did not speak; he compared our lives to the shipwrecked on a desert island. He felt the incessant weight of the physical world; he felt confusion, fear, and solitude; and he expressed it in other words: “Nature is an infinite sphere, the center of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere.” That is the text of the Brunschvieg edition, but the critical edition of Tourneur (Paris, 1941), which reproduces the cancellations and hesitations in the manuscript, reveals that Pascal started to write the word effroyable: “a frightful sphere, the center of which is everywhere, and the circumference nowhere.”

II: ABSENCE AND OBLIVION

Leszek Kolakowski, from God Owes Us Nothing:

“Despite all changes and revolutions in mentality and in institutions, we inhabit a world which increasingly displays the same characteristics and produces the same worries as those which drove Pascal to desperation. To deplore oblivion to God might seem banal in Pascal but to combine it with his other, all-pervading topic of the absence of God, was not; both resulted from our sins, but it is not absence that causes oblivion, it is rather the other way round…

…Pascal's most urgent message to his contemporaries was this: if you scratch the surface – and not very deeply – you will see that everybody is unhappy. The reasons for human misery are uncountable; but then there is perhaps only one: people have lost their ability to trust God and thereby to trust, to accept, and to absorb their own destiny. This makes them so vulnerable that the slightest failure produces in them a helpless despair. Our insecurity and anxiety are built into our very existence. The message, thus phrased, still touches the enlightened mentality of our age, a godless mentality which refuses to recognize that the absence of God continues to torment it.

The most legitimate heirs of Pascal, if often unaware of their legitimacy, are nowadays not preachers of the "religion of feeling" and not those who speak of the undefinable "leap of faith" but rather those who display to us the absurdity of a world abandoned by God. When Eugene Ionesco says that it is absurd to call his work ‘the theater of the absurd,’ because, he says, it is a theater of the search for God, he appears as today's Pascal redivivus. Those who seek God will find him, says Pascal; he even says that he who searches for God has already found him. But he also says that those who search and do not find are unhappy. He promises them good news; he is himself – with his strangely appropriate name – a carrier of this news; he knows or pretends to know how to make the message efficient by “preparing the machine”. But he also knows that it is not up to him to make it efficient: ‘Faith is not in our power’.”

III: AS THOSE WHO HAVE NEVER BEEN FREE

Maurice Clavel, from Ce que je crois:

In this present society, we are neither free not to desire, nor free – that is, capable – to satisfy our desires, and this condition does not seem to have arisen from anywhere other than us, from our own human powers. And when we protest against alienation in the name of freedom we don’t do so as people who have lost their freedom but as those who have never been free. We struggle for a freedom we cannot, properly speaking, even imagine. And in this there is a great mystery.

What is, I ask again, this freedom we have never seen, that we cannot conceive of? We know only enough about freedom to know it is something we lack. Everyone says that real life is elsewhere, nowadays, but none of us are able to say anything more, searching for an answer in drugs or artisanal agriculture, changing lives to change life – obviously, in vain. Should we say “"Nihil sufficit thee anima..." and accept that the world in itself will always be incomplete? And if we can’t, and if we can’t either, like the bourgeois spiritualists, say that the fault, the lack, is in me – what happens?

All this is to say: in the picture we just painted together, what’s new since Pascal?

…Allow me to present a hypothesis: if the bourgeois revolutions were fundamentally neither economic nor political, but cultural, the cultural revolution of the death of God in man, it would have brought into our common structures — and now finally into our common feeling — what Pascal, psychologist of the lonely individual, called the misery of man without God. In the beginning of this revolution, we would feel the lightening, the joy, the enthusiasm, the lost optimism of liberation, followed, a little later, by this feeling at the same time of gravity and emptiness, of anxiety and inertia, of shadows steadily lengthening.

But what a strange idea this is: a culture in sin….

IV: THE FIRE OF ONE NIGHT

François Mauriac, from What I Believe:

May there be in another century other men to bear homage to Pascal as we did one evening in 1962, solemnly, in the venerable Sorbonne. In those days to come, may there be another old man to rejoice over the answer that with Pascal, that thanks to Pascal, he will give to the question of Christ – the one He asked His disciples one day when almost all were leaving Him: "Do you too wish to leave me?" I alone can estimate what that edition [the 1897 Brunschvig] of the Pensées meant for the faith of adolescents of my generation. May Blaise Pascal be thanked for all those who remained faithful. These believers did not trust solely in their instinctive feelings. They accepted a piece of evidence which comes from five words written on paper and sewn into the lining of a doublet: "Nobility of the human soul." And also nobility of the human mind. All material bodies together do not have the value of a single mind. All bodies and all minds together do not have the value of the slightest impulse of charity. Blaise Pascal went before us in this ascent from bodies to minds, and from minds to eternal Love.

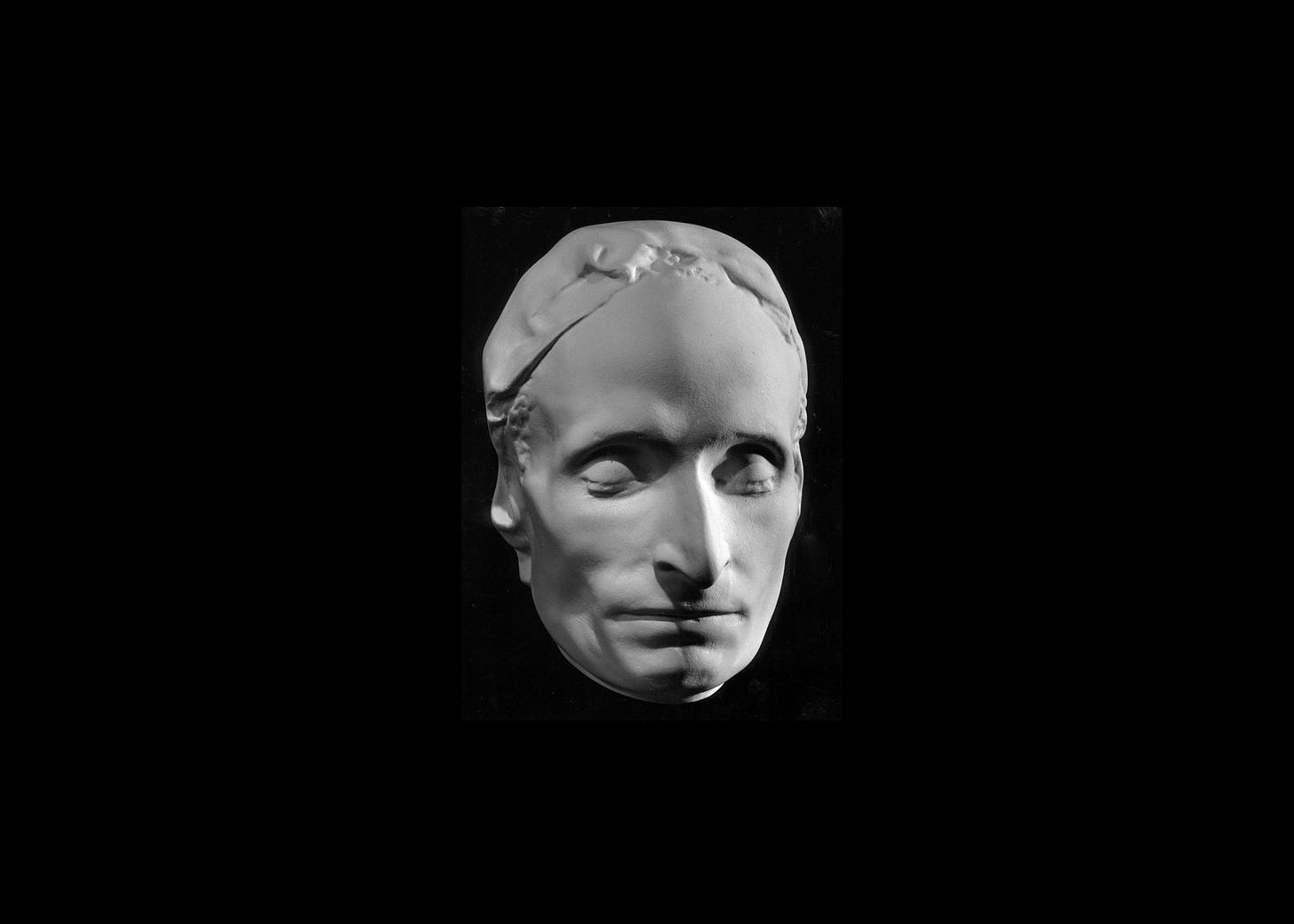

You have only to look at him. If God does not exist, where does Blaise Pascal come from? Could blind inert matter have engendered that thought and language and insatiable heart? Nothing of what the Christian believes ever seemed to me more impossible than this madness you believe.

Pascal bears witness by the single fact that he exists. It is not even necessary any more that we open the copy of the Pensées which had been given to us at school. In our closed fist we hold that invisible paper, that "Memorial" which we have never seen and yet which has not left us a single day during these past sixty years. Today we believe, as we believed at the beginning, that everything it states is true, that certainty exists, that peace on this earth can be reached, and joy. The fire of one night of Pascal was sufficient to illuminate our entire life, and like the child whom the night light reassures in his room full of shadows, because of that fire we are not afraid to go to sleep.

V: THE LIMITS OF TIME

Douglas Dunn, Reading Pascal In The Lowlands:

His aunt has gone astray in her concern And the boy's mum leans across his wheelchair To talk to him. She points to the river. An aged angler and a boy they know Cast lazily into the rippled sun. They go there, into the dappled grass, shadows Bickering and falling from the shaken leaves. His father keeps apart from them, walking On the beautiful grass that is bright green In the sunlight of July at 7 p.m. He sits on the bench beside me, saying It is a lovely evening, and I rise From my sorrows, agreeing with him. His large hand picks tobacco from a tin; His smile falls at my feet, on the baked earth Shoes have shuffled over and ungrassed. It is discourteous to ask about Accidents, or of the sick, the unfortunate. I do not need to, for he says `Leukaemia'. We look at the river, his son holding a rod, The line going downstream in a cloud of flies.

I close my book, the Pensées of Pascal I am light with meditation, religiose And mystic with a day of solitude. I do not tell him of my own sorrows. He is bored with misery and premonition. He has seen the limits of time, asking 'Why?' Nature is silent on that question. A swing squeaks in the distance. Runners jog Round the perimeter. He is indiscreet. His son is eight years old, with months to live. His right hand trembles on his cigarette. He sees my book, and then he looks at me, Knowing me for a stranger. I have said I am sorry. What more is there to say?

He is called over to the riverbank. I go away, leaving the Park, walking through The Golf Course, and then a wood, climbing, And then bracken and gorse, sheep pasturage. From a panoptic hill I look down on A little town, its estuary, its bridge, Its houses, churches, its undramatic streets.

The title of this newsletter is derived from Leszek Kolakowski’s television series on the history of philosophy, later collected into Why Is There Something Rather Than Nothing?.

Kolakowski introduces us to great philosophers through the question each asks us: Plato asks us where knowledge comes from; Augustine asks us what evil is; Spinoza asks us whether we have free will, and so on. Each thinker has his specialism; and each has, Kolakowski suggests, his limitations. The above pattern holds until we arrive at the 17th century, and the second child of an indigent tax collector in provincial France.

As for Pascal, Kolakowski tells his listeners: Pascal asks us about everything.

My New Statesman essay on Leszek Kolakowski is online here; my long profile of Bishop Robert Barron for The Tablet can be read here.

Other longer pieces of mine include an interview of the artist Peter Howson for The Tablet (link) and a review of M. John Harrison’s memoir for the TLS (link).

My TLS ‘In Brief’ review of Ralph Darlington’s book about the Great Unrest can be found here, and my Red Pepper review of Sam Miller’s book on Migration can be found here.

I’m still sick, and would appreciate prayers for my health and for my family, particularly my grandparents. In those respects I’m living in an appropriately pascalian mode: God loves so much the bodies that suffer. But good things are starting to happen, and that’s Pascal too, after all: misery and grandeur. Joy; tears; fire ☩